(9/15/09)

Clayface’s story has always been one of dependence. First it was dependence on a cream that might enable him to continue his acting career; now it is an isotope that might remedy his structural decay. But this is not simply about dependence on a curative substance; it is about the dependence of Matt Hagen, the actor. Many of pointed out the plethora of film references. Stella Bates is right out of A Streetcar Named Desire and Psycho, while Dark Interlude is a clear knock-off of Dark Victory. These in-jokes do not exist in a vacuum. They are integral to the tragedy of the story.

Recall for a moment Billy Wilder’s Sunset Blvd. Behind the superficial melodrama and happy endings of Hollywood movies, it suggests, there exists a coldhearted machine churning them out. The world beneath the movies is far less appealing than the movies themselves. Feat of Clay implied that Hagen would be without a spurned by the industry were he not able to maintain his image. Mudslide goes further. It is about the dichotomy between the perfection of the character and the monstrosity of the actor. No longer is he primarily the man and the role-player second; now he lives as an entity whose only function is to imitate. As Hagen’s senator character, so carefully defined and outlined by the script, can speak his line with heart-felt, if overly sentimental, emphasis, Hagen himself is an undefined mass, devoid of a true identity. He speaks the same line with hollowness. The manipulative tales of uplift that plagued the American cinema of the ‘40s and ‘50s are overturned in favor of a grim tragedy, still true to glorious melodramatic form.

Building on Feat of Clay's depiction of an actor in ruins are more simple moments that paint an ugly portrait of a Hollywood career. Alfred tells Batman that Hagen ran around with women of a lower intellect. The one woman he can depend on was a medical consultant on one of his films, who is now living her life as the former owner of a cheap motel. The life of supposed glamour has done nothing to benefit these characters, which now exist in a futile relationship in an eerie house on the Gotham City outskirts.

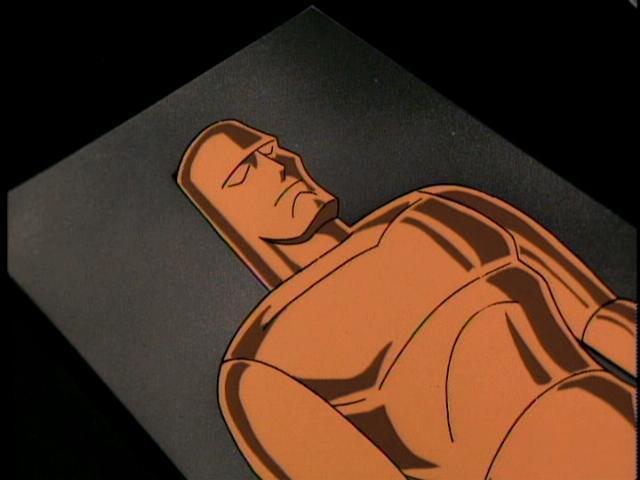

But there is something more iconic and all-encompassing about Hagen’s deterioration as it pertains to show business. He cannot even maintain his fractured, deformed self. The shell that keeps him temporarily alive is in the shape of an Oscar statue, which Hagen refers to as something that entraps him. This life as a Hollywood actor is something that has made a monster out of Hagen, and now it refuses to free him from its clutches. Hagen crumbles without it, and yet to embrace it is to be molded into a restricted, undesirable form. And while the statue is a symbolic representation of the hold that his film career still has over him, then his utter dependence on Stella, an old partner at Warner Bros., is a more literal signifier.

The hope is that this newfound isotope will permanently cure Hagen, releasing him from the bonds of this imposing shell, and letting him be an actual person again. It is here that Batman supplies the tragedy, and it is a tragedy that serves dual purposes. The first is so that the story might prove a mirror image of the happy naïve Hollywood film, a thematic effect. The second is the straightforward narrative purpose: it prevents Hagen from achieving full integrity to provoke a genuine reaction, one born of our understanding of the larger theme. He is not allowed to free himself from the bonds of his statuesque shell, and even further, cannot even achieve a basic state of uniformity. As he falls apart his identity, both as actor and character, falls with it. And all the while his clichéd dialogue proves to us that he has been fully taken captive by his imitative existence. He arrived at that existence from a human one, and now it takes him to the next step, one of total destruction.

What I admire about Mudslide is that it is a story for adults. Heart of Ice and Read My Lips, as masterful as they are, can be grasped by a thinking child. But this is in another ballpark. Only those with experience can understand its references and dual layers, all proving this to be a show that can be revisited and enjoyed in new contexts.

The episode appears to start out like your typical episode; Clayface returns, sneaks into a building in disguise, and gets stopped by Batman. Aside from a funny line from Alfred, nothing feels different from any Batman vs bad guy show. But it gets interesting. We find that not only has Hagen been growing structurally unsound, but also that he is being aided by an old actress friend of his, a woman who used to act alongside him in melodramatic Hollywood pictures. Any sense that the episode’s drama goes too over the top is quelled instantly after the viewer picks up on the various film references that begin to pop up. Stella Bates, the name of Hagen’s accomplice, is a mishmash of the Stella from A Streetcar Named Desire and the Bates from Psycho and surely enough both of these films are referenced so it’s not a ludicrous parallel. Take that and combine it with the fact that Stella spends her time watching old movie that she and Hagen starred in, and that the mold that she has constructed for Clayface in order to solidify himself bears resemblance to a certain Hollywood award all point to the fact that this episode is completely self aware of any film cliché it happens it use. As soon as that clicks, the episode becomes one of the most enjoyable experiences in all of ‘Batman: the Animated Series’.

Of course, the episode isn’t The Simpsons. These references don’t dominate the episode, nor do they undermine the serious themes the episode deals with. Even though the writers feel inclined to throw in humorous asides, what’s happening to Hagen is very dramatic indeed. If ‘Feat of Clay’ showed us the transformation of a regular actor into a monster, then ‘Mudslide’ shows him deteriorating even further. With his solidity dies his strength, and without that, not only has Hagen lost his humanity, but also he has lost any value he has ever had, both as a man and as Clayface. While Hagen has never been likable before, this actually makes him sympathetic. It wasn’t really depressing watching him turn into a monster; his career was already finished and he deserved it for his obsessive behavior. Here, however, he’s not out to steal or hurt anyone; he’s really dying in a sense.

The episode goes on to combine the over-the-top film elements with genuine sadness, as in the midst of intentionally badly scripted dialogue, Hagen falls to his apparent death. On the surface, it’s an ordinary piece of ‘Batman’ drama, but underneath it’s a humorous look at Hollywood clichés, all of which emanate appropriately from the actor who turned into a creature that could take on any identity. It’s also an appropriate mirror to the end of ‘Feat of Clay’. Both episodes play with the idea that Clayface’s defeat is the equivalent of the death scene from a movie. In ‘Feat of Clay’, he was putting on an act to mask the fact that this really was not his true end, despite the seeming seriousness of the episode’s tone. Ironically, in ‘Mudslide, he was dead serious about his problems, but they were rooted in a story that mocked the idea of dramatic climaxes and tragic demise.

With great animation from Studio Junio and a solid script full of rich detail, ‘Mudslide’ really is one of the better episodes of ‘Batman: the Animated Series’. It seems that Clayface episodes lends themselves to greatness in all areas of production.

No comments:

Post a Comment